In case you haven’t been keeping track of the anti-vaccine crowd on Twitter in the last few days, something happened that is sort of amusing. I’ll lay it out step by step:

- A man by the name of Steve Kirsch wrote an “analysis” of data given to him by the Santa Clara Health Department under a FOIA request.

- Steve-o, as he shall be named henceforth, got almost 118,000 records of people who got COVID-19 in January 2022… All de-identified, of course.

- Steve-o then used Excel to “analyze” the data and contend that being vaccinated increased your risk of getting the disease. In his data set, a variable named “NCOVPUIVaxVax” was the indicator variable for whether or not a person was vaccinated.

- Steve-o proudly showed a pivot table from his Excel analysis, but it only showed a “grand total” of about 83,000 cases. He missed 34,000 cases because the indicator variable for those cases was empty.

Okay, let’s take a pause. If you’re an epidemiologist, and Steve-o isn’t, you would have asked why you’re missing so many variables. You might even do a missing data analysis to see if the data is missing at random, missing completely at random, or missing not at random. You’re basically asking if there is something about the missing data that shows if an underlying characteristic of those with the missing variable is what is driving the missingness.

But Steve-o is not an epidemiologist. On Twitter, he claimed that the missing data would be the same as the known data in terms of vaccinated/unvaccinated proportions. That ignores the fact that COVID-19 infections are not independent of each other. The very fact that it is an infectious disease tells us that the cases could be related, and that there are underlying social and biological forces that predict if someone will catch the disease. So the data are not missing at random.

He used an example of balls in a bag, which is how we teach kids about the basics of probability, not so much the basics of biostatistical analysis of disease data.

Anyway, let’s continue…

- 6. Friend of this blog, and all around great guy, “Epi Ren” wrote on Medium.com why Steve-o was wrong, and what could account for the missing data.

- 7. Steve-o didn’t like it, and Ren told me that Steve-o called him over the weekend and texted him numerous times to set up a “debate” on who was “right.” Ren said Steve-o also sent him an email at his place of employment.

- 8. Steve-o seems to have a tendency of wanting to debate when someone says or writes something he doesn’t like. But here’s the thing, there is nothing to debate. He did not account for about 34,000 cases, and those cases did not have the data missing at random.

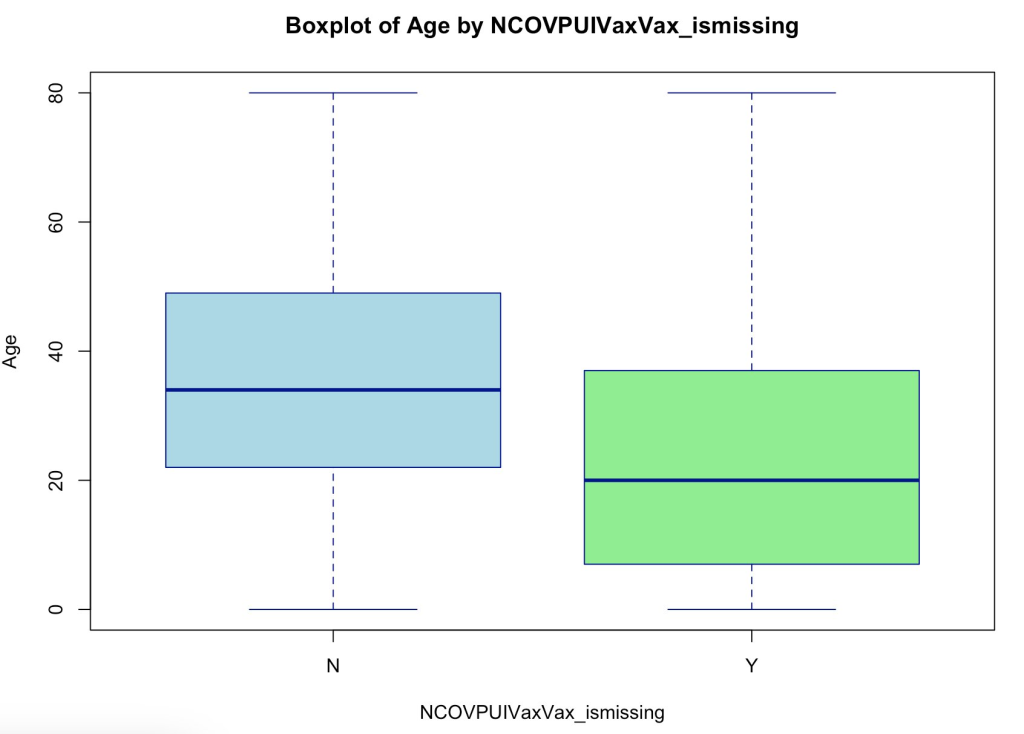

I downloaded the data as well and did my own analysis with Ren’s code, and I found that the age distribution of those with the indicator variable present and those with it missing was different. They had different average ages. I also found they had different race/ethnicity distributions. In short, there is something driving the missing variable, but we will never know without having access to the complete data set… Which would violate privacy rules and is done only by people with clearance to do those analyses: the epidemiologists at the Santa Clara Health Department.

Again, there is nothing to debate. Steve-o is a millionaire. He could go and write his own explanation for the missing data and why he ignored it. He could hire a biostatistician at about $200 an hour to do the analysis for him. But a debate to know if 2+2 equals 4? My God!

From what I’ve read, this is par for the course for Steve-o. He thinks that people will take him up on his offers of cash to do a debate. To me, it shows that he doesn’t understand how professionals in public health and other sciences work in general. We do not take bribes to have our words twisted and monetized to the frenzied anti-vaccine groups. And, knowing Ren like I do, the dude would not do it for a million or two million, or five million. He can’t be bought. But he can be reasoned with.

If someone were to point out to Ren — or any scientist worth their salt — that there is an error in their approach, I doubt they would go and call/text/email angry messages. I doubt they would call their detractors “cockroaches” like Steve-o now has.

Notice how he claims Ren is not defending his work while Steve-o does jack sh*t to defend his.

Anyway, this is probably not the first or last time you’ve heard of that guy’s antics. So we’ll keep him tabbed for nomination for this year’s Douchebag of the Year. Who knows, maybe RFK Jr. will beat him. But it won’t be by much.

What others have said about Steve Kirsch: